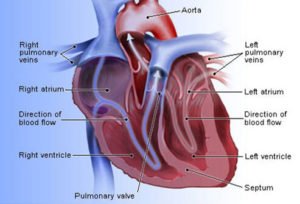

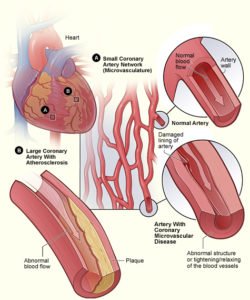

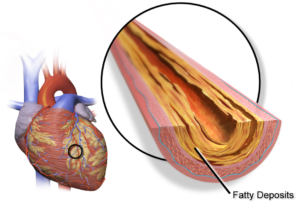

Often labeled the “silent killer,” heart disease is a leading cause of death for women in the Unites States. Yet, only 56 percent of women are aware of this fact.Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a common form of heart disease. It is caused by the buildup of fatty deposits in the arteries supplying the heart with blood and oxygen and is a leading cause of heart attacks, heart failure, abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia) and even death.

Unfortunately, women often overlook CAD because we do not experience the typical indicators that men do. Men typically experience shortness of breath or clutching chest pain while women may experience less obvious CAD-related symptoms. These can stem from less serious conditions, like heartburn or stress, when the core problem may actually be from a blockage in her heart arteries or CAD.

Because these symptoms can be easily disregarded, it is so important for women to listen to their bodies, understand and identify possible red flags, and get to the root of their symptoms.

Life-threatening differences in the way women and men are treated for heart care, persist. Two studies just out in the journal Circulation point out that despite established guidelines for heart care, women still come up short when it comes to the diagnosis and treatment of heart disease.

WomenHeart spoke to Sharonne N. Hayes, MD, director of the Women’s Heart Clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN and WomenHeart board member to learn more about why the inequities continue and how women can empower themselves and others to achieve equal and quality care for their hearts.

The classic ‘Hollywood heart attack’ is not just overdone – it’s only representative of a small portion of people, and it has allowed harmful stereotypes and health misconceptions to perpetuate for far too long.

Heart disease, typically seen as a ‘male disease,’ is actually the leading cause of death for both men and women in the U.S. In fact, the statistics are shockingly similar – in 2009 heart disease killed 307,225 men and 292,188 women, and accounted for approximately 1 in every 4 deaths for both males and females.

Yet somehow, only about 54% of women recognize heart disease as their number one threat. Because women believe that they are less likely to have heart disease, they are less likely to seek help even when they experience symptoms of a heart attack. Symptom patterns also differ by gender, with women experiencing less typical symptom patterns than men, which may also contribute to a delay in seeking medical care.

In addition, people often miss warning signs of heart disease and oncoming heart attacks. Both genders experience certain symptoms prior to a heart attack, like unusual tiredness and shortness of breath, but men can experience weakness, cold sweats, and dizziness, while women sometimes experience sleep disturbances, indigestion and anxiety for as long as a month before experiencing an actual heart attack.

The symptoms of an ongoing heart attack can vary greatly from the classic Hollywood heart attack for both women and men as well. The basic symptoms of a heart attack are similar for both genders, but certain symptoms commonly associated with male heart attacks have been exaggerated to the point of absurdity.

We’ve been taught by our favorite movies and television shows what a heart attack should look like, but plenty of real-life heart attacks do not incorporate the same hallmark traits. The typical signs of a heart attack (regardless of gender) are chest pressure, pain or discomfort, pain in the arms, back, neck, jaw or stomach, shortness of breath, light headedness, and nausea.

While a few of these are widely recognizable, many are not especially the ones more commonly associated with heart attacks in females. Women, for example, are more likely to experience symptoms like shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting and back or jaw pain instead of the arm pain we constantly see associated with men. Symptoms like these are rarely seen on the big screen, doing a great injustice not just to women, but to both genders.

While chest discomfort is the most common symptom of heart attacks in males, 10 percent of men experience no chest pain at all, and individuals with diabetes can have heart attacks without feeling any pain whatsoever.

The stereotypical heart attack simply isn’t representative of the population as a whole, but has lured many into a false sense of security by allowing people to think they can spot the warning signs and symptoms of a heart attack if they see one.

Even individuals with absolutely no symptoms or warning signs of heart disease are still at risk, and the risk of heart disease only increases with age. Overall, the I’m-falling-over-my-arm-hurts scene isn’t cutting it for anyone, and learning your medical facts from movies and T.V. is never a good idea.

WH: “Recent studies show that compared with men, women have a 50% greater chance of being delayed in the hospital Emergency Room setting, and that women are less likely to receive the same care as men in the hospital setting generally. Do these studies suggest doctors and emergency first responders are really having trouble spotting heart attack symptoms in women?”

Dr. Hayes:

“Yes. While on one hand, these findings are discouraging and reflect true disparities in care, on the other, we have to acknowledge that health care providers’ best efforts are hindered by the lack of good science about women and heart disease.

“There is no good study out there that tells us how similar or different women are from men when it comes to heart attacks. Sometimes, the symptoms are not clear, clustered differently, and can be attributed to something like indigestion or anxiety.

“If you find yourself in an ambulance or Emergency Room, don’t be afraid to say to the paramedic or triage nurse, “I think I’m having a heart attack!” You want a proper diagnosis, and a straightforward blood test and EKG are the starting points. If the thought crossed your mind that you might be having a heart attack, you need to speak up.”

WH: “Why do these differences exist in the care being given to men and women?”

Dr. Hayes:

“There are multiple reasons. Misconceptions about women’s heart disease grew roots decades ago. In the 1960s, erroneous assertions that heart disease was a man’s disease were widely spread to the medical community and to the public. This led to research almost exclusively focused on cardiovascular disease in men. Many clinical trials in the 70s and 80s excluded women or simply didn’t make an effort to enroll women in sufficient numbers to draw sex-based conclusions.

“Things are improving, because doctors are now talking more about gender and examining the process of heart disease in women. They want to provide the best care and they think that they are.

“And health care consumers are doing more too. As a patient, you can ask your doctor “What are you doing to improve the care of women with heart disease?” It’s a question worth asking. And we can’t underestimate the efforts of Women Heart and other organizations that are doing a great job of educating and empowering women to be more knowledgeable and proactive about their heart health.

“Right now, treatment guidelines help women get the care that has been shown to improve survival and long term outcomes in large groups of patients. Part of the problem now is that the guidelines are less likely to be applied to women compared to men. We know that when hospitals have systems in place to ensure they provide care according to the guidelines, women’s outcomes improve, even more than men’s.”

WH: “As researchers learn more about the physiological differences between male and female heart disease, do you anticipate doctors will begin to make better and faster diagnoses?”

Dr. Hayes:

“Yes, with the caveat that research takes time to trickle down to the bedside or patient care. The research community is good at discovering new things, but slow in putting them into practice. For example, studies in the 1990s that showed that ACE inhibitors should be used in heart failure patients took seven years to trickle down to actual patient care. Much more data is needed, and again one important way women help move the needle is by participating in clinical trials.”

WH: The most recent study in the journal Circulation shows that compared with men, women have a 50% greater chance of being delayed in the EMS setting.

A study just a month before pointed out that women are less likely to receive the same care as men in the hospital setting. Do these studies suggest doctors and emergency first responders are really having trouble spotting heart attack symptoms in women?

Dr. Hayes:

Yes While on the one hand, these findings are discouraging and reflect true disparities in care, on the other, we have to acknowledge that health care providers’ best efforts are hindered by the lack of good science about women and heart disease. There is no good study out there that tells us how similar or different women are from men when it comes to heart attacks.

Sometimes the symptoms are not clear, clustered differently, and can be attributed to something like indigestion or anxiety. If you find yourself in an ambulance or emergency room, don’t be afraid to say to the paramedic or triage nurse, “I think I’m having a heart attack.” You want a proper diagnosis, and a straightforward blood test and EKG are the starting points. If the thought crossed your mind that you might be having a heart attack, you need to speak up.

WH: Are current hospital guidelines too generalized?

Dr. Hayes:

For the most part, no. There may be a role for more individualized or gender-based care in the future, but right now, guidelines help women get the care that has been shown to improve survival and long term outcomes in large groups of patients. Part of the problem now is that the guidelines are less likely to be applied to women compared to men.

We know that when hospitals have systems in place to ensure they provide care according to the guidelines, women’s outcomes improve, even more than men’s. An airline pilot would never take off without first going over every single item on a checklist. Check-off lists help doctors and hospitals too. When providers are supported by good systems and better training the decision-making process becomes efficient and doing the “right thing” becomes easy.

WH: Why do these differences exist in the care being given to men and women?

Dr. Hayes:

There are multiple reasons. Misconceptions about women’s heart disease grew roots decades ago. In the 1960s, erroneous assertions that heart disease was a man’s disease were widely spread to the medical community and to the public. This led to research almost exclusively focused on cardiovascular disease in men.

Many clinical trials in the 70s and 80s excluded women or simply didn’t make an effort to enroll women in sufficient numbers to draw sex-based conclusions. Another reason for the differences in care is caused by physician practice and referral patterns.

Many women in the U.S. receive all or most of their medical care from their obstetricians or gynecologists. Traditionally, there has been a greater focus on reproductive and breast health in women than on their other health risks, and conversely, a lower awareness among obstetricians and gynecologists about identifying and treating signs of heart disease.

Things are improving, because doctors are now talking more about gender and examining the process of heart disease in women. They want to provide the best care and they think that they are. And health care consumers are doing more too.

As a patient, you can ask your doctor “What are you doing to improve the care of women with heart disease?” It’s a question worth asking. And we can’t underestimate the efforts of WomenHeart and other organizations that are doing a great job of educating and empowering women to be more knowledgeable and proactive about their heart health.

WH: Is there currently enough research being done specifically on women with heart disease?

Dr. Hayes:

This is a complicated subject. The lack of relevant research in women has resulted in a substantial sex-based knowledge deficit about everything from the “typical” heart attack symptoms in women, to the risks and benefits of commonly used diagnostic tests and therapies. In current cardiovascular research, we are not necessarily analyzing the data by gender and the need for gender-specific studies is not on the radar screen of researchers. Plus it is difficult to recruit women for these trials.

Women have not bought into heart disease as a “woman’s” disease, so they don’t see the relevance or potential benefit of seeking out clinical trials. But heart disease is their number one killer, so they should be clamoring to be involved in this research, just as women clamor to participate in hormone trials or breast cancer research. Talk to your doctor about what is available and consider volunteering to participate in an approved clinical trial. Many times stipends are offered and medications are provided free of charge to participants.

WH: As researchers learn more about the physiological differences between male and female heart disease, do you anticipate doctors will begin to make better and faster diagnoses?

Dr. Hayes:

Yes, with the caveat that research takes time to trickle down to the bedside or patient care. The research community is good at discovering new things, but slow in putting them into practice. For example, studies in the 90s that showed that ACE inhibitors should be used in heart failure patients took seven years to trickle down to actual patient care. Much more data is needed and again one important way women help move the needle is by participating in clinical trials.

WH: Finally, what can women and the medical community do now to improve the identification and care of women with and at risk for heart disease?

Dr. Hayes:

It is important to counter the widely held belief that women do not develop heart disease except when they’re old. Heart disease needs to be on the radar screen of every physician at every stage of a woman’s life. We need to continue to educate women and health care providers about women’s heart disease risks, symptoms and the use of appropriate diagnostic tests and therapies.

We need to see wider and more consistent use of the American Heart Association evidence-based heart disease prevention guidelines. Most important in bridging this gap in heart care between men and women, is making the medical community and the women they care for more aware that heart disease IS a women’s disease every bit as much or more as it is a man’s disease.

Here are some atypical symptoms women may experience:

- Chest pain, tightness or discomfort

- Generalized weakness, dizziness, or lightheadedness

- Nausea with or without vomiting

- Heartburn, indigestion, or abdominal discomfort

- Awareness of heartbeat

- Tightness or pressure in the throat, jaw, shoulder, abdomen, back or arm

- A burning sensation in the upper body

When it comes to your heart, even the mildest symptoms can be the biggest indicators.

For more information visit us our website: https://www.healthinfi.com

0 200

Review

-

Nice Post.....

No Comments